"Skepticism about pretty much everything is baked into my family lineage": a conversation with Derek Beres

Sit down with Conspirituality's co-host and author, learn A LOT about what you should not ask wellness to Do For You.

Derek Beres might be familiar to you as the co-host of Conspirituality, the podcast about “dismantling New Age cults, wellness grifters, and conspiracy-mad yogis”, and the co-author of the just released Conspirituality book (Public Affairs / Penguin Random House Canada).

The essays Derek publishes on Substack - under the title Trickle-Down Wellness - can be seen as an evolving blueprint for his next book, Ripped: Body Dysmorphia & Male Fragility.

The following conversation happened because of his generosity. Enjoy.

Conspirituality at large feels like this pervasive, shape-shifting entity that can and will catch people by surprise: some New Age-adjacent friends were appalled by QAnon messaging infiltrating their circles back in 2020, but at the same time they were already aware of the cultish dynamics and the potential for manipulation within certain Buddhist groups – same goes for the false belief “physical sickness can only happen because of a spiritual weakness”. (Caught me by surprise, very old news to others.) Are we going to spend decades embroiled in the - Conspirituality hydra, so to speak?

I would say we’ve long been in the hydra, to varying degrees, and will continue to be in some capacity. The pandemic obviously gave steroids to the phenomenon, but even Ward and Voas said conspirituality is cyclic, and most prominently appears in times of cultural trauma and upheaval. The most problematic aspect of the current wave is how pervasive it is, how deeply conspiratorial it is, and how much it shuns expertise in every domain. That’s the most dangerous aspect of it.

I was recently in my favorite local bookstore here in Portland, and I stumbled across a collection of essays, Examining Holistic Medicine, first published in 1985. As I scrolled through the pages, I was blown away by how current it felt, given the topics covered: homeopathy, quantum medicine, holistic methodology, chiropractic, acupuncture, and magical thinking along the lines of The Secret. The authors took a critical eye at each topic, and it felt like a half-century old version of our podcast. Finding this book reminded me that the work we’re doing has been done for a very long time, and it will (hopefully) continue, because the dissemination of good information is a necessary corrective to the dangers of pseudoscience.

I've been struck by how eloquently you've been speaking and writing about orthorexia, from the point of view of a man who struggled with it. “Orthorexia” can be defined as an excessive preoccupation with healthy food, stressing over what is truly “pure” and “righteous” eating. Now, even though we know this can become a problem for men as well as women, I get the impression "disordered eating" is still quite gendered when we talk about it. Does this track with your experience as a researcher who's been open about his own issues? Are men reaching out to you any time you publish an article, or address this on the show?

This is the topic of my next book, so I’ve been spending a lot of time with it. Eating disorders and body dysmorphia remain gendered topics, but there is more of a recognition that men suffer from these problems. Part of the reason is that more men are getting cosmetic surgeries than ever before, and younger men are using more steroids, which are both raising red flags to people who treat these problems holistically.

Eating disorders usually present in women as thinness, while in men they mostly present as being muscular. While both come with their health risks, thinness is sometimes looked down upon while being muscular is rarely criticized. That makes identifying them in men harder, and when you add in the social dimension, many men don’t even realize their keto schedule is actually disordered eating. That certainly happened to me, though in my case it was dividing macronutrients (a la “the Zone” diet).

A few men have reached out privately, and I’ve seen a few men speaking publicly on this topic, though not nearly as many as I’d like. Of course, working out and maintaining a specific diet isn’t necessarily a sign of disordered eating, but data show that many more men than suspected suffer from dysmorphia yet don’t seek treatment for it. Then again, psychotherapy used to be taboo for many men, and that has changed in recent years, so I’m hopeful that more men will publicly discuss their body image issues, as that will let other men know they’re not alone with their struggles.

"We didn’t survive cults so that Netflix vultures could monetize our shame"

These days Matthew Remski is best known as the co-host of Conspirituality, the podcast about “dismantling New Age cults, wellness grifters, and conspiracy-mad yogis” he created with fellow researchers Derek Beres and Julian Walker, so of course I found his work sometime in 2021 by searching “

I was lucky enough to talk with Matthew Remski some time ago, let me grab you a direct quote:

What Matthew calls "the survivor to crusader pipeline" very much tracks with the behaviour I believe many of us have witnessed in other fields [“Insider to Whistleblower” comes to mind]. How did you, Derek, get to a good balance in your own life and work, from longtime fitness instructor to health journalist to your current role as a writer and co-host of the podcast ? You come across as a super thoughtful dude, so clearly you have avoided the “crusader” pitfalls, or you were willing and able to course-correct in a timely manner.

I never fully escaped some of the problems we discuss on the show. As mentioned above, I suffered from body dysmorphia, mostly due to having grown up overweight and being bullied for it, which led to fad dieting and thinking that being fat is a moral failure. I never shamed anyone for their weight—given my experiences, that never entered my consciousness—but I certainly fell into the fitness ideology that anyone can just lose weight if they try hard enough, which as I now know just isn’t true.

While I thankfully don’t have issues around eating any longer, I’m still a bit neurotic about working out. My wife knows the days I miss workouts because I’m grumpier. But exercise truly calms and focuses me, and I’m not a person who overextends themselves; I rarely get hurt while working out, and that’s because I approach movement intelligently and crosstrain properly. But I still recognize how necessary it is for me to function.

As for avoiding the pitfalls, I believe it’s coming from an Eastern European family. Skepticism about pretty much everything is baked into my family lineage. My father has a very sensitive bullshit detector and I certainly inherited it. So when a wellness influencer promises something to an audience they don’t know and have never met, I’m immediately skeptical. When anyone says “I love you all” on a video I know it’s nonsense. And when they say they can heal someone when Western medicine fails, and they have no actual training in the purported field, I know there’s something dangerous going on.

An element you outline brilliantly in the book is the genuine hurt people might experience when they deal with conventional medicine – a professional doctor treats them poorly, ignores or minimises their symptoms – whereas, the alt-health circuit and its practitioners can make you feel like you matter a great deal: you're important, you deserve to be taken seriously... you're _kind of_ the center of the universe. Is there a reliable way we can learn to take care of our health without falling prey to the next "miracle cure", the next self-styled "miracle guy" that comes calling?

[A short time ago where I used to live there was a wave of unscrupulous dieticians prescribing amphetamines for weight loss – it sounds like a Mad Men episode, but it wasn't the 1950s – so of course people lost weight quickly, only to suffer from long-term imbalances, and it was very hard to get them off the drugs they weren't aware they had been taking.]

I hint at this at the end of my last answer, but to go a bit deeper, here are a few red flags:

If someone promises they can definitely cure you, run.

If they use anecdotes as proof of efficacy, remember that everyone’s biology is different and nothing works for everyone.

If they use the term “allopathic,” keep scrolling.

If they promise rapid weight loss, keep scrolling—safe weight loss is roughly a pound a week. Anything more has the potential to harm you.

If they’re selling a supplement, be skeptical. I don’t think all supplements are bad—I take lysine and B vitamins for chronic canker sores, and they work brilliantly, and I still use protein powders as part of my diet to offset my workout load—but don’t just believe what the influencer is selling. Most supplements just become “expensive urine,” and some can be dangerous.

If they attack Western doctors, move on. Yes, there are problems with our healthcare system. But I’ve had extremely compassionate and knowledgeable doctors in my life. Painting with a broad brush is a marketing technique and doesn’t reflect reality. More often than not, they’re using a rhetorical technique to get you to buy their product or service. Don’t fall for it.

There's a specific element of the "gig worker to conspiracy person" pipeline the Conspirituality book clarified for me, even though you did delve into it on the podcast: that element is the connection between the precarious life of many wellness professionals, the need to self-promote on social media and the immense network of mailing lists, resources and private groups that were already in place before they got flooded by conspiratorial content. Can someone still establish a practice without becoming a casual, accidental grifter, or is that a thing of the past?

I actually believe most people in this industry are well-intentioned. So many of my former colleagues continue to do great work in yoga and wellness, and many more will enter the field. When I see a yoga instructor offering a discount code for a CBD gummy I generally move on, even if I know that gummy doesn’t have enough CBD in it to do anyone any good. I don’t think they’re grifting; I just think they have a limited set of experiences in reading clinical studies and are doing their best to get by in a competitive industry. And while we don’t like to think of wellness as competitive, it certainly is.

We have an agreement on our podcast that we don’t punch down. Every influencer we cover has hundreds of thousands or millions of followers, and they’re constantly spreading egregious misinformation or malicious disinformation. That’s another level of grift that we feel needs to be discussed and exposed because they’re manipulating vulnerable people. I would imagine most people getting into wellness are just trying to figure their lives out and want to help other people. I would just advise that they don’t make any claims they can’t back up. The biggest problem is repeating something just because you heard someone else say it, and that road leads nowhere good.

There have been times reading the Conspirituality book I've felt a small, liberating spark - something like "ahh, now I know all this pseudo-science is just nonsense!"; other times, though, I've felt a tinge of real, quiet regret for the months I spent pursuing faddish fitness goals when I was younger (and the price tag attached to those regimes). It honestly feels like “being sad” and “coming to terms with a poor decision” is much harder than getting angry at being scammed. Do you think this might be a by-product of living in exceptionally self-centered times?

From my research, Americans have long been self-centered. That’s kind of our MO. The bigger danger is the speed that social media disseminates information, and our impulse to take things at face value just because we like someone’s vibe or aesthetic. As we say often, being an expert in one domain doesn’t mean you have anything credible to say in another, but we often see people make wild claims in adjacent (or even unrelated) fields, and because their following trusts them in one place, they extend it elsewhere. And that’s dangerous.

Giving time to somebody you don’t know is an act of generosity, so please, if you like what you’ve read, consider supporting Matthew, Julian and Derek:

Buy the Conspirituality book (US)

Buy the Conspirituality book (Canada)

Support the show on Patreon

Read Derek’s essays on Trickle-Down Wellness

You might also like:

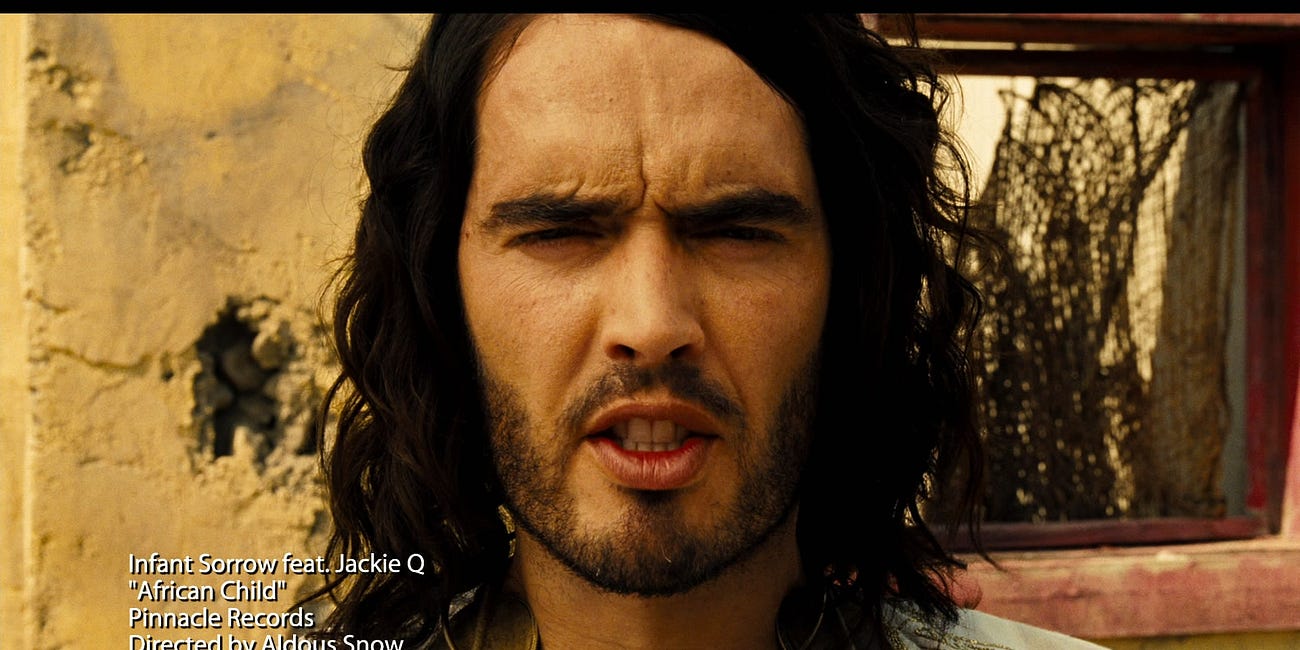

What the hell happened to Russell Brand?

On Brand is a new podcast dedicated to debunking Russell Brand: “each episode Al and Lauren dissect the ideas and antics of the man who is fast becoming one of the world's leading propagandists”. You better believe I jumped on it. Here’s my conversation with co-host

"Wake up, go again. Get a little sharper each day."

Griff Sombke is the co-host of Did Nothing Wrong, a podcast all about “politics at the intersection of extremists, propaganda and Cold War 2.0”. Didn’t we just have his partner on board? Yes, we did - that would be Jay McKenzie - but Griff is a fascinating guy with a life story that’s unique. Plus, I fucked up the title last time. And the subtitle.